Air Quality Policy

By Michelle Bai and Noah McDaniel

Understanding the Importance of Air Quality Policy

Cities account for approximately 60% of the world’s GDP, as well as being growing cultural centers. As the world becomes increasingly urban and industrialized, the quality of air in cities influences the quality of life for more people than ever before. One of the major takeaways from Habitat III, an international forum for urbanization held in 2016, is the importance of empowering citizens and increasing collaboration between levels of government.1 Cities exist at a nexus of economic growth and environmental impact and collaboration between governments, citizens, and other stakeholders is essential for developing effective and earth-friendly policy. It is imperative that greenhouse gas emissions be monitored and polluters be held accountable to provide clear air free of toxins and particulate matter to all. Without comprehensive and effective environmental policy none of this would be possible. Urban centers are critical to adapting to climate change and achieving net zero emissions.2

The solutions to air quality issues often are unique to cities and regions due to the nature of local industry, geography, and current air pollution control measures. Moreover, policy must be created to satisfy two needs: establishing global and regional standards for reducing emissions and mitigating the effects of pollution. For example, the World Health Organization has standards for the most common air pollutants. Comparing countries to these standards is an easy method of evaluating policy success. Minimizing the effects of pollution requires developing technologies to promote cleaner air and implementing proximate solutions, such as distributing breathing masks in areas with lots of particulate matter. Around the world, environmental policy, especially with respect to air quality, is being tackled in a variety of ways.

Examples of Policy Around the World

The European Environment Agency (EEA) is responsible for collecting research on the quality of air in its member states and informing member states on creating policies to ensure that air is safe for the environment and human health.3 The EEA sets standards on major greenhouse gases and dangerous air pollutants including CO2, nitrogenous and sulfurous compounds (NOx, SOx) and, more recently, particulate matter less than 2.5 microns and methane. These standards exist at what is deemed the maximum exposure to each compound before humans and the environment incur harm.4 The EAA has established air quality goals for 2020, 2030, and 2050, with an ultimate goal of 80% reduction of pollution compared to levels in 1990, when the EEA was founded.4 The EU is on track to meet the 2020 goals; however, current projections do not indicate that 2030 and 2050 objectives will be met. The current rate of progress is insuffficient. This may be in part due to 11 of 32 countries with pollution above emission ceilings.5 For data on the progress of improving Europe’s air, explore the EEA’s 2015 report here. The EEA aids members in creating policy in addition to acting as a regulatory board, with “directives on emissions trading, renewable energy, energy efficiency, and others.”3

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is an international cooperative body whose purpose is to inform policy makers. The IPCC is an international union of climate scientists and national governments established by the UN to assess the state of earth’s changing climate and how we must address it. The IPCC sets the tone for combatting climate change and has amassed a body of research valuable to policymakers worldwide.The IPCC has been critical in establishing the validity of climate change and in directing international efforts to combat it.6 The research provided by the IPCC can be used in cities and countries worldwide to determine courses of action best suited to the individual city or country. The IPCC has and will likely continue to be a key player in promoting international cooperation to mitigate the effects of climate change.

The ultimate source of legislation regarding air in the United States of America is the Clean Air Act. Section 109 of the Clean Air Act sets National Ambient Air Quality Standards, which are concentration standards for the criteria pollutants: CO, SO2, NOx, Pb, O3, particulate matter. The standards are meant to protect public health, defined as an individual’s physical well-being, with an adequate margin of safety. The secondary standards are set to protect the public’s quality of life, economic well-being, and happiness. In cities that do not attain the established goals for CO, O3, and particulate matter, a tiered system is put in place that enforces increasingly stricter standards for the industry to meet. Section 111 defines the New Source Performance Standards as category-wide federal emission standards for pollutants or a design standard, all of which are enforced through state permits.

China’s approach to addressing air pollution is seen through its law on “Prevention and Control of Atmospheric Pollution.” The administrative department of environmental protection under the State Council shall, in accordance with current national standards for atmospheric environment quality and the country’s economic and technological condition, establish new standards for the discharge of atmospheric pollutants. Individual regions may set stricter local standards after reporting to the administrative department. Units or individuals that have made outstanding achievements in the prevention and control of atmospheric pollution or in the protection and improvement of the atmospheric environment will be rewarded by the people’s government at various levels. Also, an environmental impact statement on construction projects must include an assessment of the atmospheric pollution the project is likely to produce and its impact on the ecosystem, stipulate the preventive and curative measures. Areas that do not meet the set standards are required to have the local government check and approve the total emissions of major air pollutants by enterprises and institutions and issue them permits for emission.

Elements of Successful Policy

It is imperative that each level of government take part in passing environmental policy. One of the major goals of Habitat III is to “Empower civil society, increase democratic participation across gender, age, and class lines, and encourage collaboration among all levels of government.”1 On a broad scale, international organizations such as the IPCC should be responsible for conducting research on climate change, air health issues, and collecting technological solutions. While these organizations cannot adequately prescribe policy sufficient for all nations, they are capable of making comprehensive recommendations. For example, the EEA can set emissions ceilings and develop more specific policy, as the EU is a relatively small geopolitical area.

At the level of cities and municipalities, the best environmental programs and policy are tailored to the region’s needs. For example, while most of Europe does not struggle with keeping its black carbon emissions in check, Rome and Lisbon have significantly higher emissions due to the common practice of using coal to warm houses.5 The solutions which Rome and Lisbon might pursue, then, may not necessarily apply to Paris or Amsterdam. Cities should focus on encouraging behavior complementary to the lifestyles of its residents and imposing economic regulations that take into account the needs of local businesses. This is a level of specification which can only be implemented effectively at the individual city level, but is impossible without the support and research of larger organizations.

Environmental policy must include a timeline of goals to be successful. The EEA has a detailed plan for reducing air pollution in Europe as well as discrete emissions goals. Without such a timeline, it is challenging to determine if a policy is effective. The EEA is responsible for setting standards; however, it leaves the responsibility of enforcing emissions ceilings to member nations rather than punishing violators itself. Taking action to directly punish violators instead may be a solution to the inadequate timeline progress. Additionally, the EEA should make a more concerted effort in engaging the private sector and connecting countries with technologies specified towards their main challenges. Benchmarks allow for progress to be evaluated to determine if results reflect objectives. If benchmarks are not being met, policy and implementation is likely inadequate.

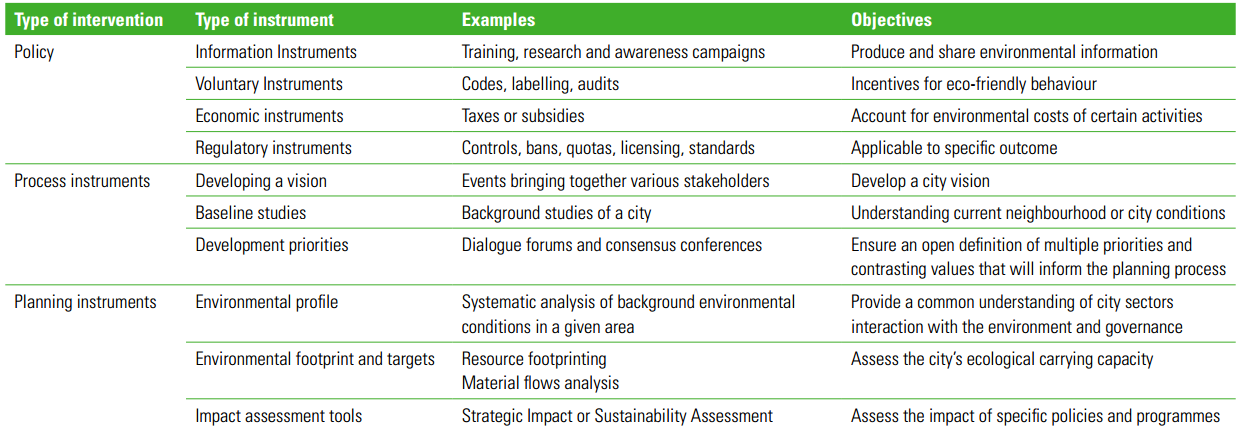

Additional elements of successful environmental policy are air quality standards, source mitigation, and methods for evaluating implementation strategies.3 The primary component of air pollution regulation is setting standards and emission ceilings. These are determined based on levels dangerous to human health and the environment. Standards set the tone for pollution control by determining which pollutants are of primary concern to a city or country. Source mitigations are strategies for reducing emissions, from all polluters. Strategies are found in many forms, as described in Table 1.

Table 1. This table describes different policy strategies using different instruments, or means of implementation. Source: UN Habitat World Cities Report 2016.

Cost-benefit analysis is a common method of evaluating the merits of a course of action, and has been used in the past with regards to environmental policy. However, cost-benefit analysis is discouraged, as it rarely favors environmental incentives, unless an advantageous discount rate is selected. Rather policymakers should use life-cycle costing or multi-criteria analysis.2 These methods look at long-term benefits and focus on the environment, rather than evaluating based on economic efficiency, as it is often the case than attempting to minimize costs often results in inefficient problem-solving.

Lawmakers must be careful to pass legislation that promotes engagement with pollution prevention. By setting more stringent standards for new sources of pollution, policy can discourage technological innovation and instead provide incentive to continue using heavy polluting machinery. It is essential that air protection laws provide a constant technology-forcing system to induce progress without lowering quality of life. It is also necessary for policy to transition its focus from end-of-pipe control solutions to pollution prevention. These systemic changes are even more important in older industries, thus policies must provide incentives to invest in environmentally friendly renovations. In the long-term it is advantageous to promote constant advancement of technology.

Effective air pollution policy implicitly includes technology-forcing incentives. The key to developing a long-lived solution is to incorporate innovation into the statute itself. In the United States Clean Air Act, separate standards are set for new and existing polluting sources, with new sources facing much stricter regulations. The unintended result of this decision was the discouragement of technological innovation and the encouragement of the extended life of inefficient machinery. Had the act imposed equally harsh standards on new and old sources, there would have been more incentives for industries to invest in cleaner technology. Consequently, it is necessary that future legislation provides no loophole for older technology to stretch its life to the detriment of the environment.

Developing Future Air Policy

The effectiveness of a law is correlated to the specificity of standards. The more a policy leaves up to ambiguity, the more it is interpreted on the side of environmental degradation. It is of utmost importance that policymakers work with experts in the field throughout the legislative process for policies to produce results. An objective scientific voice grounded in evidence must be the basis of effective legislation.

It is not possible to create a universal set of public policies for every nation in the world. Each country’s unique geography, political layout, and financial status contribute to its attitude toward air quality. There will always be opposition to strict air quality standards, such as from the fossil fuel industry, lobbyists, and businesses whose expenses would increase as a result of environmental legislation. The weight of their voices affects the actual legislation produced. Similarly, air quality regulation is deeply rooted in the strength of the government. For example, India has the world’s most polluted air. According to Yale and Columbia’s Environmental Performance Index a major contributing factor to the status of air quality in India is the government’s inability in enforcing its standards.

Developing environmental policy which is equitable, balances the interests of governments and businesses, and is economically feasible is a monumental task. Air quality is no exception. Especially in urban areas it is imperative that air pollution be minimized and that policy be tailored to the constraints of a city or municipality. Promoting technological development, establishing stringent but enforceable standards, and setting timelines for reaching goals will make policy more successful. By combining the research and standards of international bodies with the solutions unique to a locality, air pollution in cities will be of reduced concern in the 21st century.