Food Accessibility

By Agni Kumar

Introduction

The demand for high quality, safe, nutritious processed foods will continue to increase as the global population and affluence increases. This imposes an enormous burden on the environment, and the food processing industry has responded by making progress in reducing the carbon and water footprints of products and the amount of waste generated. However, to ensure that the food processing industry is economically and environmentally sustainable, it is important to take an integrated approach of the whole food supply chain, from the initial farming stage and production and transportation of goods.

Recent projective models indicate that in order to feed the world’s growing population, global agriculture will have to double its food production by 2050. 1 However, with more farming results more environmental harm – a combination of clearing land, burning fossil fuels, consuming water for irrigation, and spreading fertilizer contribute to the overall effect. Thus, simply doubling current practices, which would inevitably ruin large areas of land and poison rivers and oceans, is not an option. Both macro-scale and micro-scale solutions are proposed below, encompassing the effects of improved food affordability and distribution on nutrition levels and current healthy food access measures.

Food Accessibility Programs and Solutions

Food Affordability

Examining the environmental footprint of the food system.

It is important to minimize the environmental footprint of the food system and improve nutrition by making food supplies more diverse, nutritious and sustainable. This means rebalancing production from monocrops, 2 cereals, dairy, and meat towards the more diverse production of fruit, vegetables and semi-arid nutritious crops that use less water and are more tolerant of heat.

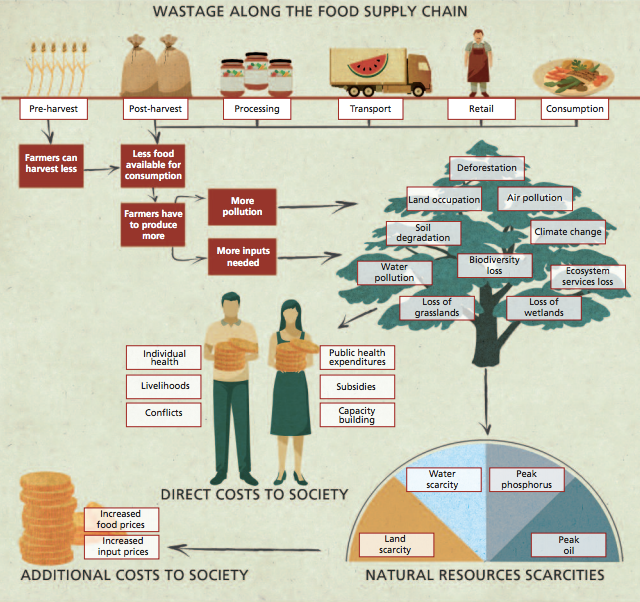

Figure 1. According to a study by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), many of the costs of food waste come from resource loss and other environmental impacts of agriculture. Since much of the world’s resources are used to produce food (40% of its land, 70% of its freshwater, and 30% of its energy), 3 every piece of food that is thrown away represents wasted resources.

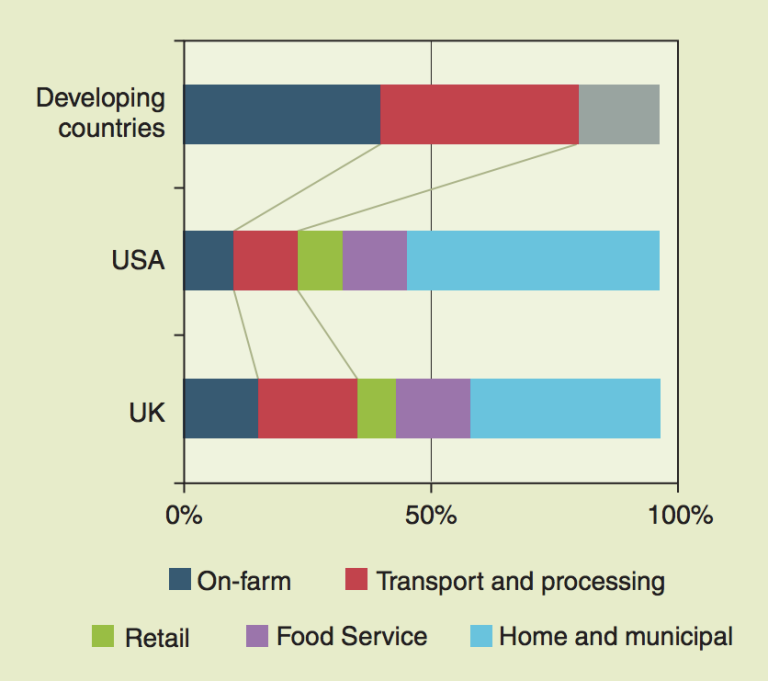

Where along the supply chain food is being wasted varies widely between developing and developed countries. In wealthy, developed nations like the United States, food is wasted mostly at the consumption stage. There are several reasons for this – for one, advanced technology in agriculture as well as food processing and distribution means that food is plentiful and cheap. Americans spend less of our income on food than most other countries in the world (6%, strikingly different from the 43% in Egypt). 4 On the other hand, in poorer, developing countries, food wastage is more concentrated toward the production side. Lacking technology and infrastructure for transportation and processing is indicative of increased crop losses due to pests, spoilage, and weather. Methods to improve shelf life such as pasteurization and refrigeration are almost always absent in places where food is locally grown. The keys to solutions that address both types of nations lie in improving food literacy and the efforts of NGOs to implement specialized programs on a large scale.

Figure 2. This chart from a 2010 food security report 5 compares the sources of food waste in developing countries to those in developed countries. It is shown that food waste that occurs on-farm and during transport and processing is the largest contributor in developing countries, whereas home and municipal food waste dominates in developed countries.

It has become increasingly evident that city governments should do more to motivate and support businesses to improve their environmental performance – particularly at the level of primary production, which generates many of the food system’s most pressing environmental impacts. Governments should inform producers of the potential benefits of adopting beneficial management practices (BMPs). Currently, a main barrier to BMP adoption is concern about cost, yet fully 61% of producers adopting BMPs actually found that the financial benefits exceed the costs (while only 10 per cent incurred net costs). 6

Improving household food waste literacy can also go a long way in reducing food waste. Education and awareness campaigns, perhaps organized by community volunteers, could help address many of the causes of consumer food waste, including confusion over “best before” and “use by” dates, the preparation of too much food, and purchasing more food than the household needs. In addition, low food prices are clearly connected to high food wastage. Stores tend to overstock their shelves while throwing out unbought foods. USDA standards 7 call for any produce with a blemish or irregularity to not make it into the food supply, so farmers are forced to leave such produce to rot in the fields. Fruits and vegetables make up the majority of this on-farm food waste, which is a significant contributor to food waste in developed countries.

In an attempt to mitigate the costs that food waste incurs on developing countries, both governmental organizations and NGOs should bring improved technology and methodology into food production, storage, transport, and marketing. Notably, the efforts of NGOs in helping to reduce food waste have taken many forms – through charity work, the gleaning of unharvested food from farm fields and redistribution of unsold food from grocery stores to food shelters have been encouraged. Moreover, the startup company Leanpath produces technology to help retailers monitor their waste, which causes stores to realize the financial cost of wasting food and subsequently leads to decreases in food waste. Similarly, in the United Kingdom, a widespread campaign by the Waste and Resources Action Programme (WRAP) 8 has increased public awareness so that food waste is now a major topic of discussion and thought.

Food Distribution

Transportation and Packaging Costs, Food Banks

A proposed model to optimize the efficiency of local food distribution engages farmers’ market associations and managers to perform key organizing functions to distribute locally grown foods to institutions through farmers’ markets. The model will utilize a central hub market for collecting, storing, grading and distributing food sold by the farmers’ market association or market manager on behalf of its member farmers. The ultimate goal of the project would be to advocate for the development of permanent farmers’ market structures with the infrastructure to facilitate wholesale and retail distribution as well as processing of local foods. In general, central hub markets are geared toward providing producers with access to larger volume markets. Food hubs provide a single drop-off and pick-up point for produce to be distributed to consumers, restaurants, hospitals, and other large businesses. Additionally, food hubs can improve access to healthy foods in low-income or underserved areas by making it easier for farmers to offer their products in such areas, while also providing producer services such as insurance, quality control, and distribution and processing.

Objectives of the proposed program include the building of a model around existing management and association structure, assisting farmers’ markets in developing wholesale and specialty food programs, and connecting multiple markets to larger ones. The program also aspires to provide technical assistance and outreach to farmers in order to meet packing and grading standards, build institutional awareness about local food purchasing programs run by farmers’ markets, and assist institutions in the development of local food programs. The program is likely to develop market distribution infrastructure and processing capacity through efficient resource allocation.

Other solutions to the food distribution problem may come out of newly-opened areas in materials science research. Packaging can often be reengineered to reduce package weight or bulk, which can translate into savings in raw materials, landfill impacts, and transport and storage energy use; but extra costs may be incurred elsewhere. For example, Kimberly-Clark is working with Safeway to pilot palletless deliveries of paper products. 9 This is likely to allow trucks to be packed with more products, although labor costs may increase as a result. Publicized and funded research efforts would aid to balance these factors.

Food Deserts

“Food deserts” are geographic areas where access to healthy, affordable food options (particularly fruits and vegetables) is restricted or nonexistent due to the absence of full-service grocery stores within a convenient traveling distance. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) 3 defines a convenient traveling distance as more than one mile in urban areas, and more than ten miles in rural areas, estimating that nearly 23.5 million people live in food deserts, of which 13.5 million are low-income residents. Food access issues affect urban and rural areas alike – solutions must go beyond the idea of simply building more grocery stores, as both rural and urban food desert areas have a hard time attracting and keeping commercial grocery retailers.

Community solutions include garden initiatives, which are quickly popping up in both urban and rural areas and provide easy access to inexpensive, fresh produce. The American Community Garden Association (ACGA) 10 provides resources for over 18,000 community gardens in the U.S. and Canada. Moreover, after a survey 11 revealed that 94 percent of residents would purchase more fresh produce if it were available at convenience stores, the city of Minneapolis enacted the Minneapolis Health Corner Store initiative, requiring all corner and convenience stores to stock a certain amount of fresh fruit on their shelves. Results closely aligned with those in the aforementioned survey.

Additionally, Mobile markets and produce trucks have popped up in many underserved areas. In California, Second Harvest Food Bank 11 has been using a refrigerated truck to distribute fresh produce to those in need since 2006. In Detroit, Peaches & Greens, 12 a mobile produce truck, delivers fruits and vegetables to a high-need community. Garden on the Go, 13 a produce truck initiative from Indiana University, makes 16 weekly stops, sells produce at an affordable price, and accepts food stamps, making access to healthy fruits and vegetables as convenient as possible.

Healthy Food Access Measures

Measure of number of grocery stores, supercenters, farmers markets, fast food restaurants, and convenience stores on a per 1,000 population basis.

According to the Center for Rural Affairs, 14 one in five grocery stores has gone out of business in the last four years in rural areas. Because of this, many realize that there is not a uniform solution to the food desert issue, and as a result have implemented varied and innovative strategies.

Notably, when social entrepreneur Brahm Ahmadi was unable to engage the interest of private investors, he began selling stock directly to the public in order to fund a new grocery store. People’s Community Market 15 provides a full-service neighborhood food store as well as a health resource center and community hub to the 25,000 West Oakland residents that have limited access to fresh produce. Moreover, in California, a new public-private partnership loan fund called Fresh Works 16 works with a $200 million dollar investment pool to provide loans and grants to grocers wanting to build or expand in underserved neighborhoods.

Conclusion

Mission 2020 believes that, with regards to bettering food accessibility, increased public awareness can help begin to shift strongly ingrained habits and mindsets surrounding the value and consumption of food. Consumers themselves are the greatest contributors to the food waste problem in developed countries, but we should also be a central part of its solution. Simply appreciating the food production process and giving attention to our purchasing and discarding habits can go a long way.

However, the implementation of programs is also necessary to distribute more effectively the nearly 40% of food that is currently being thrown away. 17 Through a diverse range of non-profit and volunteer, policy measures, and household-level food literacy program, we hope to steadily reduce food waste and costs of food distribution to increase food availability in developing and developed countries alike.