Inclusionary Zoning Policy

Problems faced

Cities encounter a problem of inadequate affordable housing supply.1 Urban developers deem housing to be affordable if it is available at a price affordable to low–income groups.2 An adequate affordable housing supply is important in the effort to maximize the equity of cities around the world by the year 2050. One method of increasing the supply of affordable housing is the implementation of inclusionary zoning policies.

Inclusionary zoning is a powerful policy encouraging or requiring urban developers to create a proportion of affordable housing units within a new housing project.2 This type of policy is powerful because of its customizability; a city can modify the characteristics of its policy to agree with local circumstances such as its economy, policy, and history. However, there are possible adverse effects of inclusionary zoning, and policymakers and city planners should note the trade–offs of the policy. These include an increase in housing prices and a decrease in housing supply, which can be slightened if certain cautions are taken. As another example of policy trade-offs, alternative–compliance options allow some freedom to the developers while still requiring compliance but can impede the development of a beneficial type of housing called fair housing. Overall, implementation of inclusionary zoning policies has the potential to produce desirable levels of affordable housing and social integration by 2050.

Recommendations

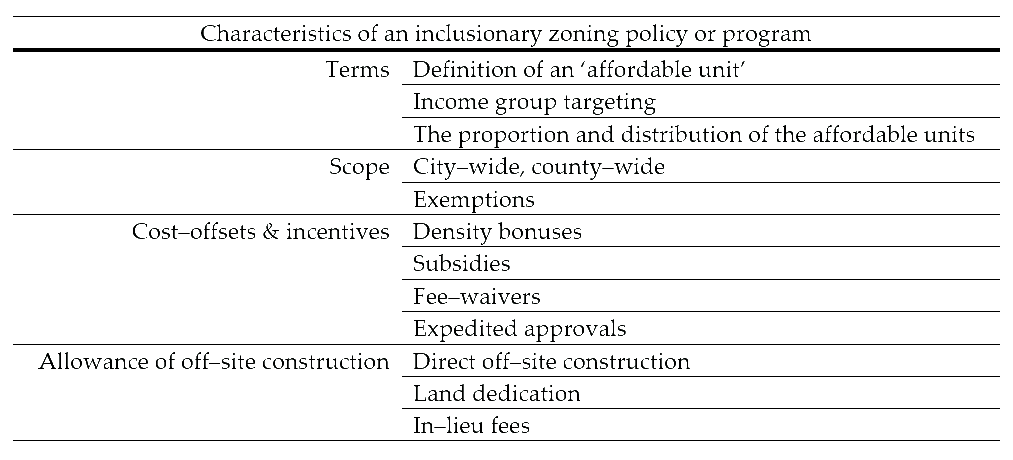

A city chooses several properties for its inclusionary zoning policy (see Table 1): the required proportion and distribution of affordable units, how strict the policy is, what projects the policy applies to, and the list of alternative–compliance options and cost–offsets, among others.2,3 For instance, programs generally prefer city planners to create affordable housing units on–site, within the same building as the wealthier units called market–rate units.4 As an example of an alternative–compliance option, some policies allow developers to pay a fee, called an in–lieu fee, in place of constructing affordable housing units. Another alternative–compliance option is land dedication, where a developer donates land of equal value to the city’s market–rate land for affordable housing development.

Table 1. Some of the many properties an inclusionary zoning program or policy can modify in order to fit its city’s conditions.

In an interview, Ted Schwartzberg, Senior Planner of the Boston Planning & Development Agency (formerly known as the Boston Redevelopment Authority), discussed density bonuses, which are a common type of cost–offset. In the context of inclusionary zoning, a density bonus permits a developer more floor space, to build taller buildings, or a higher limit of housing units, in exchange for the developer incorporating affordable units.5

Using data collected from previous surveys, Schuetz et al.,3 found correlations between inclusionary policy exemptions and affordable housing production suggesting ordinances that exempt smaller projects and offer density bonuses produce more affordable units.2,3 The policy can cause adverse effects on the housing economy under certain conditions, however. Developers do not wish to pay for providing affordable housing, so the supply of housing overall declines, and this in turn causes housing prices overall to increase.2

An aspect of an inclusionary zoning ordinance that can minimize these adverse effects is the length of time the policy has been in effect. In the case of the San Francisco area, its programs that have long been in effect resulted in only slight negative effects on housing prices and production, while more recent programs in Boston yielded a smaller amount of affordable housing.3

Planners and policymakers should approach these conclusions with caution, though, as most cities fail to update records, provided they have any, and the customizability of inclusionary zoning programs makes it difficult to determine correlations.3 Furthermore, location is a substantial variable; some cities produce more affordable housing units through chance alone, again making it difficult to determine correlations.

Overall, if jurisdictions offer a combination of cost–offsets, exempt smaller housing projects, and remain effective for substantial time, then the adverse effects can become slight. Due to the limited data on inclusionary zoning, they should structure their region’s programs carefully and record the results of their policy, adjusting it accordingly.

Fair housing

While alternative–compliance options — namely off–site construction, land dedication, and in–lieu fees — are part of an inclusionary zoning policy’s flexibility and help to lessen adverse economic effects, they also result in a trade–off between affordable housing and fair housing. Fair housing in this case refers to residential housing developments enabling integration. Integration is either “actual, authentic human interaction between people of different races and economic classes and overcoming ‘social distance’ ” or “better or equal access to good schools, good jobs, [decent shopping, healthy neighborhoods], etc.” or both.4 Co–location with the wealthier housing units, called market–rate units, ultimately determines if fair housing will be produced. Builders generally favor affordable housing over fair housing when alternative–compliance options are present. If the developer chooses to build affordable housing off–site, then the land will not likely be located with the market–rate housing. If the developer chooses to dedicate property for affordable housing, then the land will also not likely be located with market–rate units. And if developers choose to pay fees in–lieu of on–site development, the affordable housing units produced are likely to be located where costs are lower.4 With alternative–compliance options, urban developers will produce affordable housing, but will likely not supply fair housing and support integration.

John Fernández, head of the MIT Urban Metabolism group, discussed the idea of implementing affordable housing near green spaces. Encouraging the implementation of affordable housing near quality parks and green spaces could be a valuable strategy for producing both affordable housing and fair housing, as low–income neighborhoods generally do not have the benefits of these areas compared to other neighborhoods,6 and this strategy would improve integration and the health of their residents (see Health and Air Quality and Green Spaces for information regarding the benefits of green spaces). Cities may desire fair housing production because increasing a city’s population density means commuters are able to live near their places of work and leisure. The increase in use of walking and biking and decrease in non–sustainable forms of transportation, along with the reduction in commute time of the average worker, improves a city’s transit efficiency and health (see Sustainable Transportation for information regarding sustainability of transportation). Additionally, a socio–economically diverse population provides a variety of services, because low–income and high–income populations each require, patronize, and provide different services. This compact diversity bolsters the economy.5,7 Policymakers should encourage the production of affordable housing near parks and green spaces in order to produce both affordable and fair housing with the additional benefits of increased health and improved economy.

Defending inclusionary zoning policy

As a notable example of an inclusionary zoning trade–off, alternative–compliance options can impede integration, but they can also help the policy stay in effect. Providing alternative–compliance options allows a city to uphold an inclusionary policy’s legality, because the developer may view the policy as less demanding.4 Therefore, if a city anticipates a legal challenge, then it should consider including alternative–compliance options. Virginia’s courts limit the power of the local government to adopt zoning policies not authorized in the state enabling act.3 Iglesias4 sees legal attack on inclusionary zoning as a “framing contest,” meaning the two parties argue what type of policy the courts should view it as. Opponents may challenge a jurisdiction by framing inclusionary zoning as a tax, a fee, an exaction, or rent control while the local government will generally see it as a land use regulation. They do this because these more complex types of ordinances require stricter tests of legality.4 In order to justify an impact fee as exaction, for example, a local government will need to conduct an impact study under the appropriate law. In order to prove an ordinance rationally addresses the governmental objective to provide affordable housing, a local government will need data and analyses illustrating that this is the case. See Iglesias4 for a more complete picture of this idea.

Final thoughts

Inclusionary zoning is a powerful tool allowing planners and policymakers to tune their programs according to the local economy, residents’ preferences, and local political environment. A city uses it to increase the supply of affordable housing and also as a means to engender social integration. Though there is risk for slight adverse effects, this simply suggests the need for careful construction of the local policy. An inclusionary zoning program offering only on–site development of affordable units seems to be best for producing both affordable and fair housing, and it is possible for this type to be legally defensible. There is a deficit of data and inferences and knowledge of its mechanisms and effects regarding inclusionary zoning, so one should regard most suggestions with caution. The implementation of policy, the political structure, the existing market, and even local residents affect the outcome of policies, making it difficult to perform analyses even with data. Additionally, a city does not require an inclusionary zoning policy to produce affordable housing, many other policies and programs may yield affordable housing and fair housing, but using inclusionary zoning in coordination with these other policies and programs has worked well within several US cities, including San Francisco, Boston, Los Angeles, and Chicago.2 Although much of the practice of and information available on inclusionary zoning is within the United States, governments outside of the United States should find it possible to create a legal and effective policy in much the same way. Anywhere worldwide, urban planners and policymakers should track the progress of their city’s inclusionary zoning measures. This includes the production of affordable and fair housing — both on and off site — and how it affects the market. They should customize the policy according to this feedback, the local policy goals, economy, and general preferences, for the best results.