Health Impacts of Urban Air Quality

By Claire Halloran

Although air pollution is often associated with climate change and the environmental problems it causes, air pollution also poses a serious health threat in cities, where there is a high concentration of both air pollution and people. Indeed, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that outdoor air pollution was responsible for 3 million premature deaths in 2012.1 People in developing countries are particularly susceptible to these adverse health effects: 88 percent of those 3 million premature deaths occurred in low- and middle-income countries.1 Immediate effects of high air pollution levels include damage to respiratory cells, added stress to the heart and lungs, and aggravated respiratory and cardiovascular illnesses. Issues associated with long-term air pollution exposure include loss of lung capacity, decreased lung function, increased incidence of respiratory diseases, and accelerated lung aging.2

Different air pollutants, including gases and particulate matter, have unique short-term and long-term effects on human health. Due to the varying severity of health effects for different pollutants, the WHO and United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has maximum concentration recommendations for each substance. Addressing each of these health problems that arise by achieving these recommended concentrations requires knowledge of each pollutant’s direct sources and the sources of their chemical predecessors. In the following paragraphs, I will examine the different sources and health effects of various air pollutants.

Ozone

While a robust ozone layer is necessary for terrestrial life, high levels of ground-level ozone can trigger serious respiratory issues and damage the respiratory system.1,2 In cities, mobile pollution sources, such as cars, and industrial emissions produce nitrogen oxides and volatile organic compounds. In the presence of sunlight, these compounds react to produce ozone.1,2 Ozone is a respiratory irritant that causes airway constriction as well as long-term lung damage and disease at concentrations higher than 100 μg/m3 (that is, concentrations of ozone over 100 micrograms per cubic meter).1,2 See Table 1 for an exhaustive list of ozone’s health effects and Table 2 for the WHO and EPA guidelines for ozone levels.

Nitrogen Dioxide

In addition to catalyzing the formation of ground-level ozone and other air pollutants, nitrogen dioxide is itself toxic in high concentrations. Even short-term exposure to nitrogen dioxide in concentrations exceeding 200 μg/m3 can inflame airways, and long-term exposure to concentrations as low as 40 μg/m3 reduces lung function (For a full list of nitrogen dioxide’s health effects, see Table 1).1 Meeting the WHO guidelines for nitrogen dioxide concentration (listed in Table 2) primarily involves restricting combustion reactions, which produce most nitrogen dioxide.1 In urban areas, traffic is another important source of nitrogen dioxide.2

Sulfur Dioxide

Sulfur dioxide causes the most rapid health effects among gaseous pollutants: just 10 to 15 minutes of exposure at 500 μg/m3 can irritate the respiratory system and cause coughing, wheezing, shortness of breath.1,3 Although sulfur dioxide exposure has serious health effects, human action can lower its concentration: approximately 99 percent of sulfur dioxide in the atmosphere can be attributed to human activity.3 Burning fossil fuels, processing mineral ore, and other industrial processing of sulfur-containing materials produce the majority of sulfur dioxide.1,3 Of these processes, fossil fuel burning is the most common in urban areas because of their large power needs.

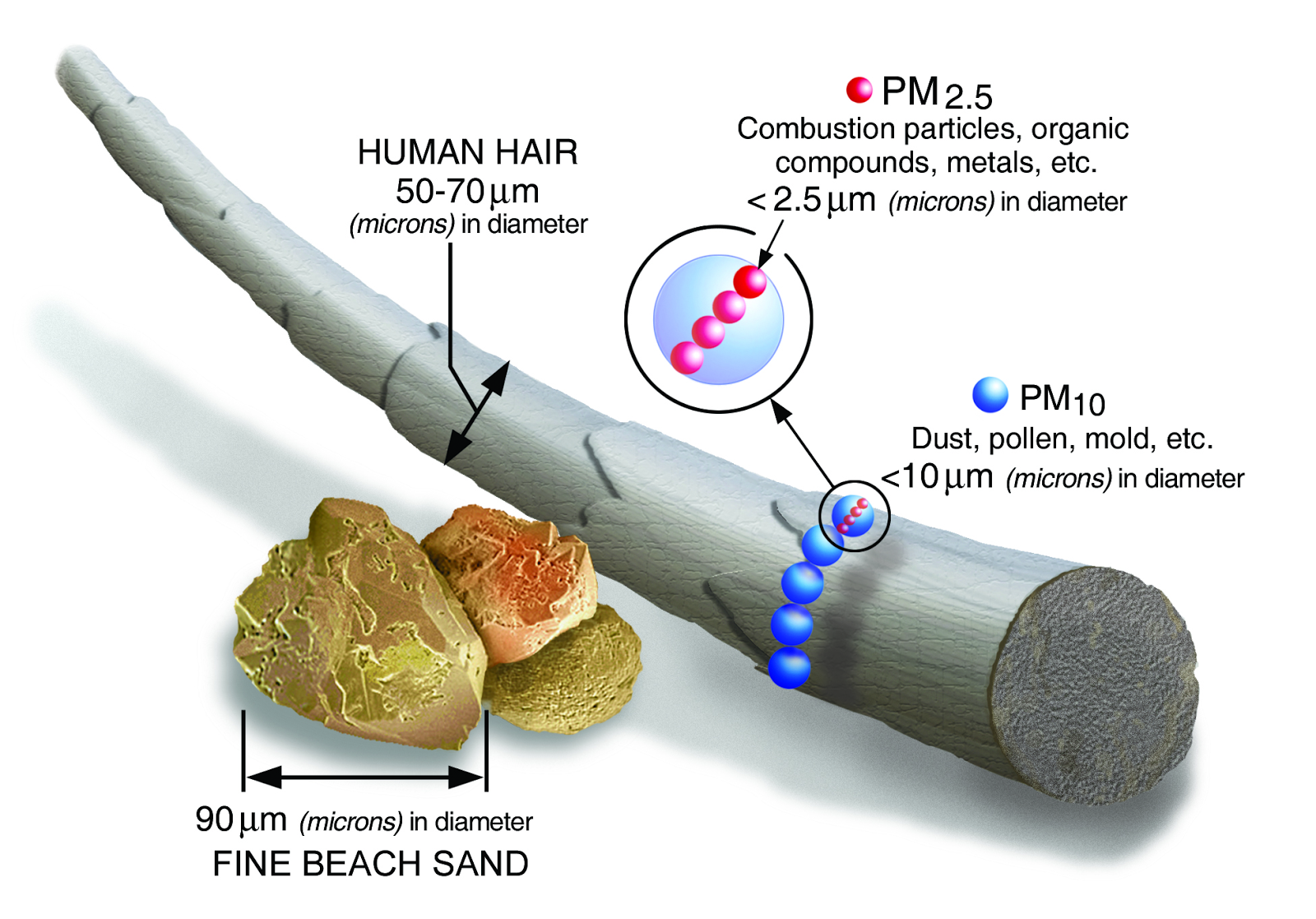

Figure 1. Size comparison of particulate matter types, PM10 and PM2.5. The minuscule size of particulate matter allows it to damage the lungs and enter the bloodstream.1,4,5 Source: US Environmental Protection Agency.

Particulate Matter

Particulate matter, the complex mixture of substances suspended in the air, is the air pollutant that contributes the most to human health problems. In fact, the WHO found that particulate matter is the air pollutant most closely associated with cancer, especially lung cancer.1 Sources of particulate matter vary greatly by region, and major components of particulate matter include sodium chloride, black carbon, sulfates, ammonia, nitrates, mineral dust, and water. However, the lethal power of the particulate matter comes from its size, not from its composition.1,5 While particulates larger than 10 microns in diameter can be filtered out by cilia and mucus in the nose and throat, particulate matter smaller than 10 microns in diameter, known as PM10 (10 micron particulate matter), can lodge inside the lungs.1,4 PM10 can harm the respiratory system by settling in the lungs and bronchi, and particulate matter less than 2.5 microns in diameter, known as fine particulate matter or PM2.5, can enter the alveoli and thus enter the bloodstream (see Figure 1 for comparison of particle sizes).2,4 Exposure to such particulates at concentrations as low as 50 μg/m3 for PM10 and 25 μg/m3 for PM2.5 for only a day can cause respiratory irritation and difficulty breathing (see Table 2 for WHO and EPA concentration guidelines).1,2 Long-exposure to particulate matter at concentrations as low as 20 μg/m3 for PM10 and 10 μg/m3 for PM2.5 can lead to serious cardiovascular and respiratory problems and premature death in people with heart or lung disease (see Table 1 for a full list of particulate matter’s health effects).2 However, health damage has been observed at every concentration of particulate matter, so concentrations of PM should be kept as low as possible.1 Although the main sources of urban particulate matter vary widely based on region and level of development, but traffic is one of the most important sources, accounting for 25 percent of emissions on average.5

| Ozone | Nitrogen Dioxide | Sulfur Dioxide | Particulate Matter |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short-term effects | |||

|

Triggered asthma, bronchitis, and emphysema Constricted airways Breathing problems Increased susceptibility to infection Increased fatigue |

Inflammation of airways |

Irritation of nose, throat, and airways Irritation of eyes Inflammation of airways Coughing, wheezing, shortness of breath Tightness in chest For some asthmatic people: Respiratory symptoms Change in pulmonary function |

Irritation of eyes, nose, and throat Coughing, chest tightness, shortness of breath Aggravated lung disease Increased susceptibility to respiratory infection In those with heart disease: Heart attacks and arrhythmias |

| Long-term effects | |||

|

Damage to deep portions of lungs Reduced lung function Lung disease |

Increased symptoms of bronchitis in asthmatic children Reduced lung function |

Decreased lung function Aggravated asthma Chronic respiratory disease in children Development of chronic bronchitis and obstructive lung disease Irregular heartbeat Heart attacks (nonfatal) Lung cancer In those with heart/lung disease: Premature death |

|

| Table 1. Summary of health effects associated with and caused by various air pollutants. While all pollutants are detrimental to public health, particulate matter causes the widest variety of pressing health effects, both long- and short-term.1–3 | |||

| Pollutant | Averaging Time | EPA Level | WHO Level | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ozone (O3) | 8 hours | 0.070 ppm (140 μg/m3) | 100 μg/m3 | |

| Nitrogen Dioxide (NO2) | 1 hour | 100 ppb (188 μg/m3) | 200 μg/m3 | |

| 1 year | 53 ppb (100 μg/m3) | 40 μg/m3 | ||

| Sulfur Dioxide (SO2) | 10 minutes | N/A | 500 μg/m3 | |

| 1 hour | 75 ppb (197 μg/m3) | N/A | ||

| 3 hours | 0.5 ppm (1310 μg/m3) | N/A | ||

| 24 days | N/A | 20 μg/m3 | ||

| Particulate Matter (PM) | PM2.5 | 24 hours | 35 μg/m3 | 25 μg/m3 |

| 1 year | 12.0 μg/m3 | 10 μg/m3 | ||

| PM10 | 24 hours | 150 μg/m3 | 50 μg/m3 | |

| 1 year | N/A | 20 μg/m3 | ||

| Table 2. EPA and WHO standards for various air pollutants for public health protection. The WHO standards tend to be more conservative than EPA standards.1,6,7 | ||||

Air pollutants from a variety of sources pose severe health risks, especially in urban areas where both population and pollution is dense. Given the serious and immediate threat that air pollution poses, city officials must implement solutions to protect urban populations. By maintaining the WHO’s standards for air quality, cities can avert serious public health crises.