Food Welfare and Equity

By Ginny Sun

Introduction

Food poverty is defined as “the inability to afford, or to have access to, food to make up a healthy diet.”1 Recent studies have found low-quality diets to be directly related to poor health and disease, contributing to 30% of all early death and disabilities.1 In fact, diet is the leading cause of cancer, accounting for approximately one-third of cancer deaths. In addition, diet quality causes almost half of all chronic health disease (CHD) deaths, increases the rate of falls and fractures in older people, and leads to lower birthweight and increased childhood mortality. Individuals with lower incomes suffer most from poor diets due to their lower intakes of fruits and vegetables and their higher consumption of salt and saturated fats.1 With food poverty having such detrimental effects on the health, well-being, and success of individuals, it is important to develop welfare programs to ensure people living below the poverty line are still able to afford a nutritious diet.

When designing programs to alleviate food poverty, one must consider why individuals are unable to eat a nutritious diet before tackling the problem head-on. People living in food poverty come from a variety of different countries, backgrounds, cultures, and occupations, and therefore face different problems concerning food access and affordability. When analyzing the United States alone, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) had varying effects on different racial groups—dietary quality did not improve as much for black and Hispanic adults than for white adults.Researchers suggest that residents from underprivileged minority neighborhoods are less likely to have access to healthy meals even if they are able to afford them.2 Therefore, different programs must be designed in order to target as many individuals living in food poverty and reach our goal of ending hunger and malnutrition by 2050.

The following programs can be divided into two categories: macro- and micro-scale. Macro-scale programs are nationwide solutions that alleviate food poverty, involving the federal government and international organizations by giving out welfare assistance to anyone who qualifies for it. While large programs are generally effective at decreasing the cost of food to low-income families, they apply to such a large group of people that they do not account for individual needs and special circumstances. Therefore, macro-scale programs must be supplemented by micro-scale programs, which can serve as “fixes” for larger programs that may unevenly distribute food to the poor. Our solution to ending global hunger and malnutrition is to combine local and national policies and programs to create both depth and breadth in the fight to end food poverty.

Macro-Scale Food Welfare Programs

Food Stamps and Subsidies

In most countries in the world, federal governments offer some form of aid for the poor to be able to purchase food. In these types of programs, individuals who earn less than a set amount of income are eligible to apply for food subsidies. Supporters of food subsidies point out the substantial amount of evidence demonstrating how recipients of food aid increase their food consumption. In addition, the subsidies given out to the poor end up benefiting the farmers who produced and sold the food, thereby stimulating the entire market as a whole.2,3 Critics however, say that the high administrative costs and the possibility of fraud or abuse is not worth a large-scale food welfare program, and free handouts may cause individuals to be disincentivized from working.4 In order to determine whether or not the benefits of food stamps and subsidies outweigh their costs, we analyzed the primary food welfare program of the United States, SNAP.

The United States federal government’s Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), formerly called the Food Stamps Program, provides assistance in purchasing food for low or no-income households (See Figure 1). It is the largest program administered by the Food and Nutrition Service, maintaining a budget of $74.1 billion in 2014 and serving approximately 46.5 million Americans.5 The USDA distributes SNAP benefits to households based on their size or income through specialized debit cards known as Electronic Benefit Transfers, or EBTs, which can be used to pay for food at supermarkets, convenience stores, and other food retailers.5

Figure 1. Logo of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, which is administered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) under the Food and Nutritional Services (FNS).5

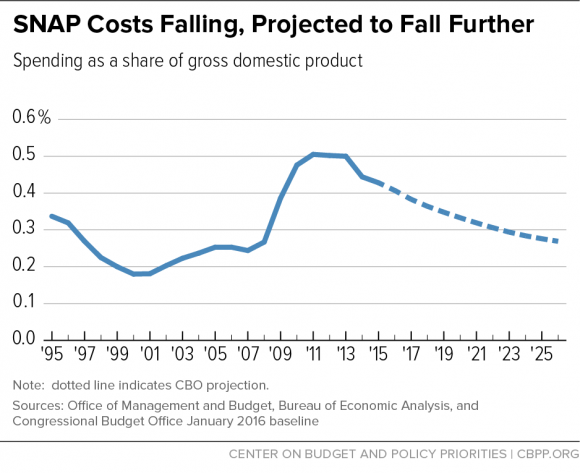

According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, SNAP has been effective in meeting the needs of low-income individuals. While it notes that the amount of spending in SNAP has increased since the recession of 2008, the growth is only temporary and and will fall as the economy recovers (See Figure 2). In addition, SNAP reaches approximately 75% of all eligible individuals and has one of the highest payment accuracy ratings of social programs.3 Researchers estimate that SNAP has decreased the number of people living with food insecurity by 30% and has taken 2.4 million children out of severe poverty. The USDA also estimates that every $1 billion invested into SNAP creates $340 million in farm production, 8,900-17,900 full-time jobs, and $1.8 billion in economic activity.6 Therefore, SNAP not only provides food benefits to the very poor, but also boosts entire rural and urban economies as a whole.

One of the major points of criticism regarding SNAP is that EBTs can be used to purchase food items with low-nutritional value. In a study by Yale University, researchers found that approximately $2 billion of SNAP funds were used solely for sugar-sweetened drinks.7 However, other researchers report that SNAP participants had a lower rates of obesity than adults who did not receive SNAP benefits but had the same level of food insecurity. They concluded that SNAP participation “appears to buffer against poor dietary quality and obesity,” although adding that it benefited white adults and Hispanics more than other racial groups.8

The United States’s SNAP is one of the largest federal welfare programs and therefore draws much controversy and criticism. Many believe that such programs should either be reformed or given greater budgetary constraints. For example, Michael D. Tanner of the CATO Institute, a conservative think tank, notes how the SNAP program cost $60 billion in 2013 as opposed to $18 billion back in 2000, yet 18 million American households still experience food insecurity.4 However, many other economists point out that the cost only takes up a small percentage of the GDP while covering 46.5 million Americans,5 and the cost of the program will decrease as the economy continues to improve.3 Researchers analyzing the efficiency and effectiveness of SNAP show that the benefits of SNAP and similar food welfare programs generally outweigh the cost of their implementation.2,3

Figure 2. The cost of SNAP spending has increased over the past few years, especially due to the economic recession of 2008. However, the cost of SNAP is projected to fall in the future.9

In addition to the United States, many countries around the world already have well-developed food subsidy or stamp programs dedicated to fighting hunger and malnutrition. While research has shown these programs to be beneficial, governments can conduct more experiments to fine-tune the programs and achieve maximum efficiency. For example, the Indonesian government recently experimented with their food subsidy program, Raskin, or “Rice for the Poor.” The experiment demonstrated that providing mailing cards containing information about the program to eligible households increased the total subsidy received.10 Following Indonesia’s example, governments around the worlds should analyze the efficacy of their own food welfare programs and determine in what areas they need improvement. In developing countries, where local corruption and “leakages” are prevalent, central governments should provide greater oversight over local leaders to ensure the proper distribution of food subsidies. In more developed countries, governments could attempt to integrate food subsidies with electronics, such as cellphones or electronic cards, which would decrease the administrative costs of the program. By making minor changes to the program, central governments can ensure the welfare program runs smoothly at a lower marginal cost.

Cash Transfers

In recent years, cash transfers have garnered attention from the economic and political fields, with several studies and programs yielding a positive correlation between cash transfers and dietary nutrition. The idea behind cash transfers is simple: provide grants of money to welfare recipients with little or no restrictions on what they can use it for.11 While skeptics claim that the poor could use these free handouts for the purchasing of temptation goods, such as drugs, alcohol, or tobacco, advocates of cash transfers say that it gives the poor more freedom of choice and cuts the administrative costs of alternative in-kind transfers, such as distributing food to poor households.11

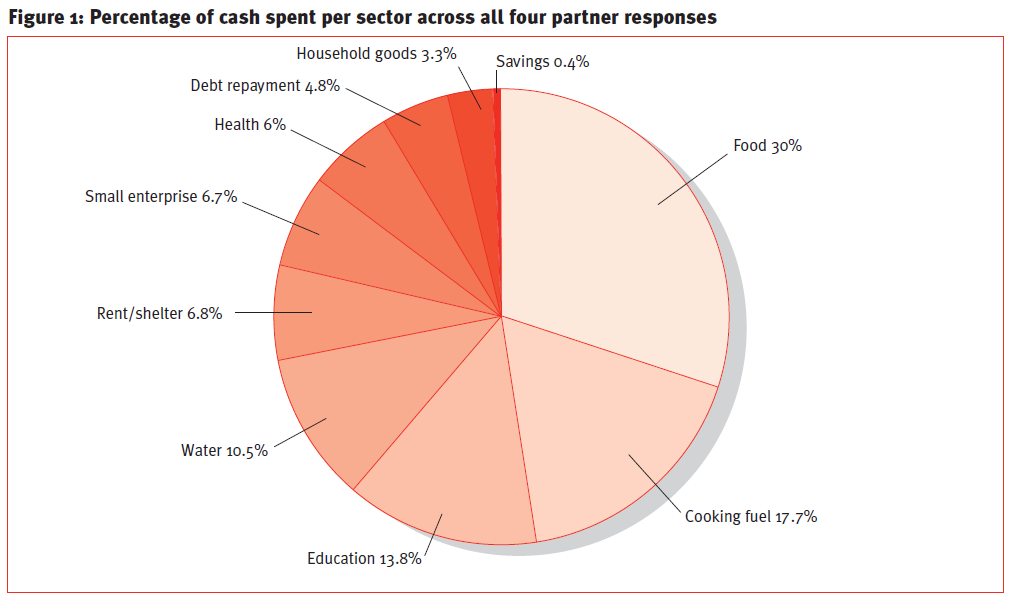

Separate studies in rural Mexico, Zimbabwe, Malawi, Ecuador, Yemen, and Haiti showed that unconditional cash transfers (UCTs) had a profound effect on poor individuals (See Figure 3). In Mexico, for example, researchers gave cash transfers to some households and in-kind transfers to others. Perhaps surprisingly, cash recipients did not spend more on tobacco or alcohol when compared to those who received only in-kind transfers, but both treatment groups saw the same improvements in nutrition and child health. In addition, giving out food cost 20% more to administer, while the cash transfers also aided with schooling, medicine, and transportation.11 Similar experiments in cash transfers found similar beneficial effects, with no significant change in the amount of temptation goods being purchased.11 Overall, UCTs ultimately led to higher dietary diversity and food frequency as well as decreased the psychological stress of poverty-stricken individuals.

Figure 3. A study on UCTs in Haiti demonstrates the spending patterns on beneficiaries. Individuals spent on a diverse range of beneficial goods and services, such as food, education, and health.12

A concept similar to an unconditional cash transfer is a universal basic income (UBI), in which every resident of a country is entitled to a regular sum of money. A theoretical model of UBIs, in which every American over 21 years would receive $10,000 a year, was shown to in fact be cheaper than all the U.S. state and federal welfare programs combined due to lower administrative costs.13 In the 1970s, parts of Canada and the United States ran a series of experiments in UBIs. In both countries, the results showed positive results, including reductions in child malnutrition, increased school attendance, and decreased hospitalization rates while having little impact on employment rates.11,14 However, it is important to note that these studies were conducted decades ago and abandoned after governmental changes,14 suggesting that UBIs may have little political feasibility in some countries.

Critics of UBIs point out that by replacing current social programs targeted towards the poor, federal money originally targeted towards the poor would be shared by the middle and upper classes.15 Therefore, the impact of the program on those who need it most could potentially be reduced. Since cash transfers are different from UBIs in that they are only given out to the poor, rather than all individuals, the money from the transfer is directly targeted towards the poor. At the same time, cash transfers still offer the flexibility in purchasing power that UBIs offer. Therefore, cash transfers will still result in the same positive effects such as better health, nutrition, and education that UBIs offered.

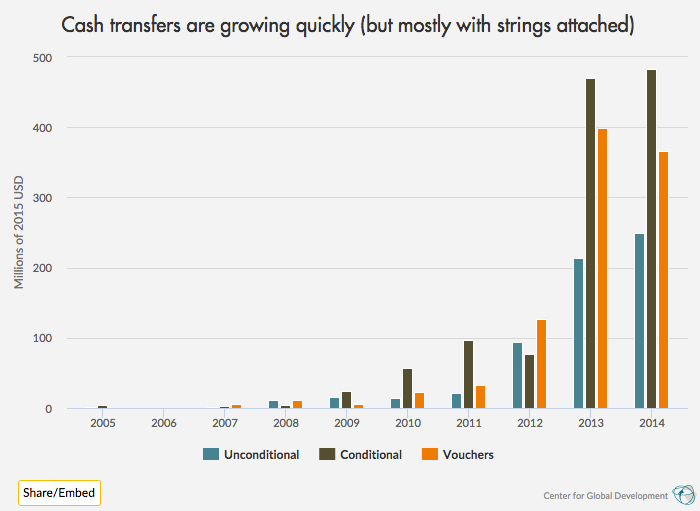

The biggest problem with unconditional cash transfers is gathering the support to pass laws in favor of it. While the activities of NGOs and charities such as GiveDirectly have shown such transfers to be successful on a relatively small scale, many are still afraid that the program may not function as well on a larger scale and longer amount of time due to the higher probability of corruption or abuse.11 In addition, in certain political climates, governments may be against the idea of free handouts. However, the cash transfer can be modified to suit a country’s specific needs and requirements. For example, in cases where unconditional transfers are unsupported, conditional cash transfers, such as giving cash in return for sending children to school, could be seen as more favorable (See Figure 4).

Figure 4. Both conditional and unconditional cash transfers have grown dramatically within the last decade. While UCTs require less administrative costs, conditional cash transfers may be more practical, as they present a “middle ground” between in-kind transfers such as food subsidies and unconditional cash transfers.16

The main differences between the types of macro-scale food welfare programs are the amount of control on the actions of the aid recipients and the administrative costs of the program. With food subsidies or stamps, the benefits would focus solely on the purchasing of food. While this would increase administrative costs, the program would have the narrow focus of increasing food consumption and possibly nutrition, depending on the implementation of the program. With unconditional cash transfers, the poor would have more freedom in determining how to use their money instead of being restricted to purchasing food items. Studies have shown this money not only improved dietary health, but also increased school enrollment and household assets. In addition, there was no increase in the amount of temptation goods purchased. However, not enough long-term UCT programs have been implemented to show the long-term impacts on unconditional cash transfers on the poor.

Our recommendation for countries attempting to eliminate food poverty by 2050 depends on the initial condition of the food welfare policies in place. If an established, well-known food subsidy program is already in place, such as in the United States, we suggest keeping the program in place, as the fixed costs for its implementation have already been paid for. However, food subsidy programs can continuously be improved upon to maximize efficiency. Some methods of improving a food subsidy program is to digitalize the transfer of money between the consumer and supplier through mechanisms such as EBTs or increasing the access to healthy food options.

For countries with less developed welfare programs, they could experiment with unconditional and conditional cash transfers, as many developing countries in Africa and Central America have recently attempted. Since the government itself may lack the funding to create a large-scale cash transfer program, it can work with NGOs, World Bank, and other charitable organizations to develop one. Cash transfers require less administrative costs than in-kind transfers and are therefore more cost-effective, so developing countries may favor this option more. However, it is important to note that since cash transfers are a relatively new concept and are still controversial, governments should ensure they have support from both sides of the political spectrum before launching such a program. Therefore, the program will be sustainable even when the political climate within a country changes.

Micro-Scale Food Welfare Programs

Food Banks

Food banks are charitable, nongovernmental organizations that distribute food to those who have difficulty purchasing or gaining access to food. There are multiple varieties of food banks around the world. Most follow the “warehouse” model, in which food banks, located in large cities, store large quantities of nonperishable supplies and later distribute it to smaller communities or government agencies, such as orphanages, soup kitchens, homeless shelters, etc. while others distribute food directly to the poor.17 Overall, food banks are welcomed for their charitable donations to help feed the poor living in or near cities. However, research shows that food banks are not as effective as government-run welfare programs.18 Click here for more information on food banks.

Local Markets

Low-income neighborhoods often lack grocery stores and farmer’s markets that provide fresh produce to their house. The lack of healthy food options is due to their higher costs in comparison to processed foods, which may deter food retailers to expand into poorer communities.19 One particularly innovative way of delivering nutritious foods to underserved neighborhoods is through temporary farmer’s markets that are easy to set up and move around. One example of such a market is Greensgrow Farms Mobile Markets, located in Philadelphia. These mobile markets are set up on food trucks and can be transported throughout several neighborhoods in a single day with minimal set-up required.20 Therefore, these markets bring fresh and healthy products at low prices to the economically disadvantaged in the city who would normally be unable to access fresh produce.

Figure 5. While many farmer’s markets, such as the Sweetwater Organic Farm in Florida, accept SNAP, there are still others that have not worked with the local government to accept Electronic Benefit Transfers.2 Source: Sweetwater Organic Community Farm

Another method of increasing fresh food access to underserved neighborhoods is by creating government-subsidized farmers markets in certain parts of the cities. Local governments should allow farmers to sell fresh produce on certain government properties, such as parks or community centers near target communities, at no additional cost. This policy will decrease the cost of set up, causing the the location for a market there to seem more appealing. In addition, more efforts should be raised to make farmers markets compatible with national food welfare programs (See Figure 5). Currently, in the United States, not all farmers markets accept SNAP, mainly because EBT machines are expensive to install and maintain.21 Therefore, the poor may be unable to purchase the fresh produce offered at the market.

While the popularity of farmer’s markets has increased over the past few years, more can be done to deliver the fresh produce from such markets to low-income neighborhoods. As shown by organizations such as Greensgrow Farms, markets that provide healthy food options are beginning to expand into underserved communities. However, in order to increase their beneficial impact on the poor, governments and NGOs should provide incentives for organizations to set up markets in certain neighborhoods. These incentives include providing an EBT machine, giving a one-to-one match on SNAP dollars spent, or offering a free venue near poor neighborhoods. These programs will not only increase the accessibility to fresh produce of low-income households but also absorb part of the fixed cost of running a market. Therefore, sellers will be able to decrease the prices of their foods, which allows households to purchase produce at a more affordable rate as well.

Food Recycling

Large amounts of fresh produce go to waste every year. Especially in developed countries, unsold food products are simply thrown away even when they are still fresh or of good quality. By setting up charitable organizations that purchase leftover foods and sell them to those in need at a lower cost, we can ensure less food goes to waste and is instead given to those living in food poverty. Click here for more information on food recycling.

Micro-scale projects are small scale, local solutions to helping feed the poor and hungry. These projects help provide high-quality foods at a lower cost, allowing individuals living in poverty to have greater accessibility to nutritious foods. Overall, micro-scale projects are much cheaper to implement than national, macro-scale policies and receive support from both sides of the political spectrum. Therefore, even if the government changes over time and causes fluctuations in the spending on federal welfare policies, individuals can work together to fight hunger and malnutrition within their local community.

Conclusion

Mission 2020 believes that in order to create sustainable and equitable cities of the future, we must ensure that hunger and malnutrition is eradicated throughout the world. At both the local and national level, much can be done to alleviate food poverty and ensure equity in terms of food affordability and accessibility. In order to create a sustainable city, one must first guarantee that its occupants are healthy and productive by eliminating hunger and malnutrition. In order to accomplish this goal, federal governments must develop a food welfare program to help lift individuals out of food poverty or find solutions to maximize the efficacy of the program if it already exists. In conjunction with a national program, individual cities and communities should provide resources to increase accessibility to cheap, healthy food options by decreasing the cost of food distribution. Overall, solutions of different scales must be implemented to combat food insecurity that allow poor households to purchase nutritious foods as well as distribute such products to underserved neighborhoods.